Jennine Tambio teaches the Research Capstone course for the College of Liberal Arts & Sciences (CLAS) at Lesley University. In this fully online course, students develop a senior research project based on an area of interest in their major. They synthesize the knowledge and experiences they have gained from prior courses through research, discussion, peer review, and reflection.

This summer, Jennine taught her SU1 and SU2 courses in Ultra Course View. Ultra is Blackboard’s newest version, redesigned from the ground up. It has several advantages including a more modern look, consistent navigation, progress tracking for students, streamlined grading, and more.

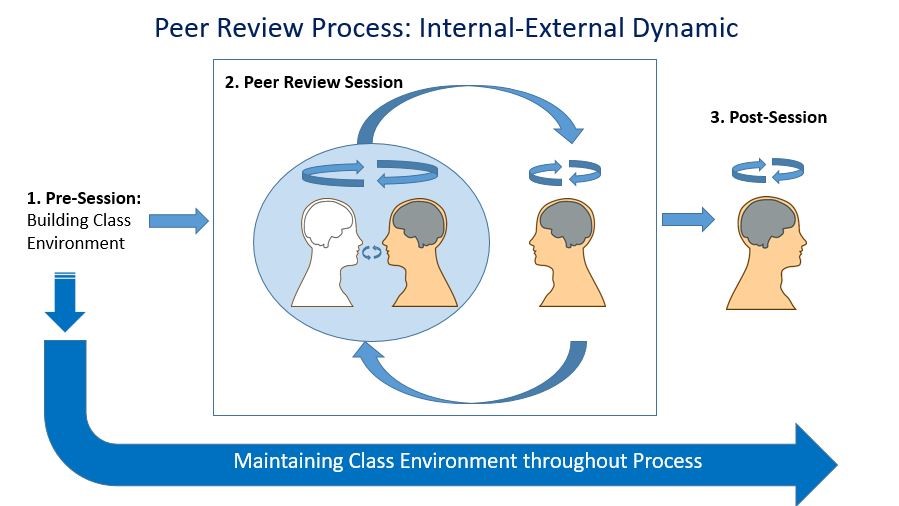

eLearning and Instruction Support (eLIS) at Lesley approached Jennine about piloting Ultra courses due to her heavy use of peer review. Previously, she had been using an external tool called PeerGrade which provided a robust framework for students reviewing each other’s work using rubrics. While Jennine liked PeerGrade, it required purchasing a subscription and the company was beginning to phase out its use in favor of a newer product. The Ultra Course View includes the option for peer review directly in its assignment tool. No additional tools required. Jennine also thought it looked cleaner and easier to use.

To get started, eLIS set up and transitioned the first few weeks of the course. Jennine quickly took over creating the subsequent weeks with guidance from eLIS. She had a couple of minor questions that were quickly answered while learning the new environment, but nothing significant. As part of the transition, she consulted with eLIS on how to reorganize parts of her course to make it concise and easier to navigate. She also worked to turn the narrated Powerpoints she had previously created into Kaltura videos making them more accessible for her students and captioned.

The resulting Ultra courses were very successful. Jennine got a lot of compliments from her students who “thought I had just made a beautiful Blackboard course.” Her students “were all able to hop in and seamlessly navigate” the course.

“It’s much cleaner, fosters more collaboration because of the format. The peer review feature was really cool and I loved that part of the course.”

“I enjoyed how easy it was to see what was due each week and to check them off!”

“I like Ultra Course mode much better.”

– Student survey responses

The process of transitioning her course helped her to “improve the quality and delivery of the course.” The peer review tools in Ultra were easy to use and allowed her to see each student’s submission, their feedback to others, and the self-review of their own paper all in one space. The students didn’t need to navigate to another site and learn another tool. And Jennine didn’t need to pay for a subscription.

According to Jennine, “It’s not a stressful transition.” While recreating her course took a little time, she appreciated the opportunity to rethink, update, and finetune certain aspects of her course. She found the final result more visually appealing. Her students were very engaged and she discovered helpful tools and nuances for a better teaching experience.

Interested in learning more about the Ultra Course View and if it is right for you? Contact elis@lelsey.edu.