February’s Community Conversation focused on Peer Feedback, led by CLAS and LA+D faculty Kim Lowe, Summer Clark, Lisa Spitz, and Bill Porter. They are members of a long–standing research group that looks at ways to implement and improve peer review and critique and to “create a better learning experience.”

Kim Lowe kicked off the conversation by explaining how she had hated peer review as a student and had vowed, “when I became a professor, I would never do it.” However, she saw the learning benefits and found the peer review protocol the group created highly effective for her students.

Creating the Peer Review Protocol

In 2016, the interdisciplinary group began to study peer review by researching best practices for conducting peer feedback assignments, the benefits of peer feedback, and how to address challenges. The benefits of peer review include self-reflection, self-regulation, critical thinking, and communication skills that transfer not only to other classes, but to students’ professional careers. It enhances empathy and students’ ability to navigate social and emotional interactions in the classroom while exposing them to perspectives and opinions other than those of their instructor.

Peer review also requires students to participate at a higher level of engagement. They must spend time and energy to provide constructive feedback that the other student can utilize. However, students may not trust the feedback they receive from other students and may not be sure if they should apply it or not. Students may even doubt their own ability to provide feedback.

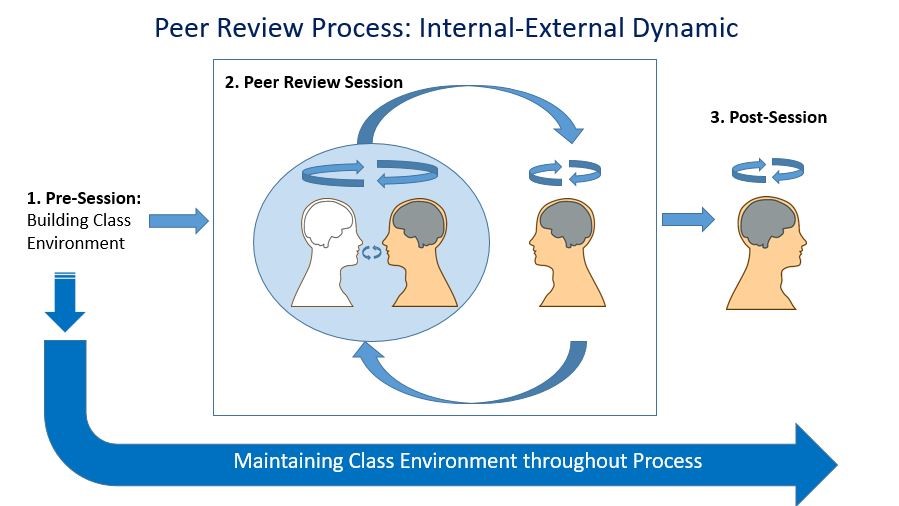

Due to these challenges, the first stage of the peer review protocol the group developed is to prepare students to do peer review. In this stage, the instructor builds trust in the process by discussing the strengths of peer review and, perhaps even more importantly, the reasons why they may be skeptical. Faculty should also discuss how peer review will be used within the class and model what effective peer review looks like. It’s also important to assess the feedback given, not just the assignment being reviewed.

The second stage, the peer review session, is a scaffolded dialogue where students submit their assignment, identifying the areas where they most want feedback. Other students then provide feedback using a rubric or by answering a series of questions to guide their feedback. Students then review the feedback they received, rewriting it in their words to encourage processing, and determine how or if they will apply it.

In the final stage, students revise their assignment. They also submit a summary noting how they implemented the feedback they received and the reasons why they made those choices. The instructor then assesses both the assignment and the student feedback.

Q&A

One question asked of the group was if peer review was spreading beyond art and literature courses. Summer Clark spoke about using peer review to help her education students create better lesson plans and believes that it can be used across disciplines. The group encourages faculty to co-create criteria for reviewing work in order to create consensus and understanding around what qualities embody good work, regardless whether that work is a drawing, essay, presentation, or business analysis.

However, that was just the beginning of the discussion, which included brainstorming strategies with the other attendees. Watch the recording to hear more and join our Faculty Community Conversation Team to continue chatting.